Print 6: The Aqueduct (On exhibition at the Winnipeg Art Gallery until May 21, 2023).

'This is Freedom Road'

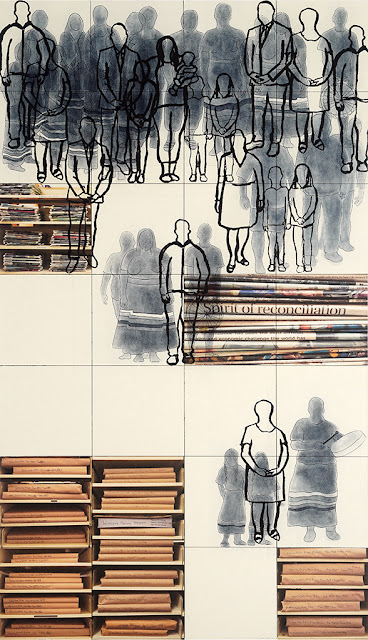

The last two prints focus on efforts of reconciliation and restitution.

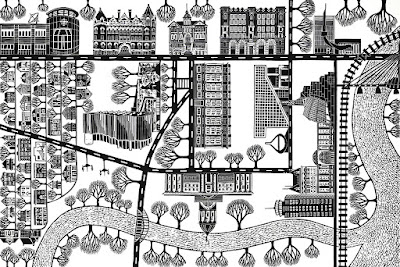

This print chronicles the construction of Winnipeg's Aqueduct from explorations of Shoal Lake in 1906 to reparations made to the Indigenous community so deeply affected by this.

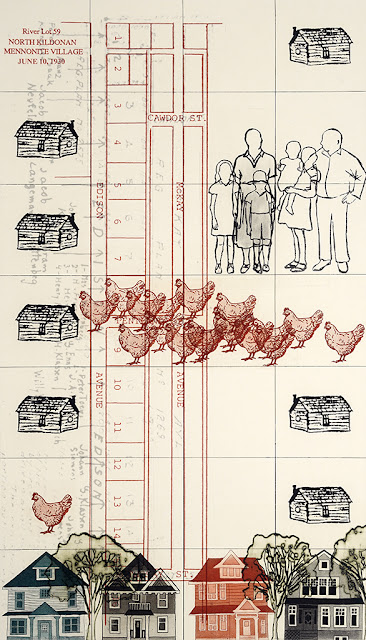

The background of this print is a digitally printed map of the trajectory of the Shoal Lake aqueduct from 1918. Centrally located are the houses of Winnipeg, while the Indigenous families of Shoal Lake No. 40 are pushed to the margins as we have seen in previous prints; their houses and homes are upended sideways along the edge of the paper. Behind the city of Winnipeg you can see large figures of politicians and settlers, printed on the backside of the paper, representing the powerful decision makers in the colonization projects.

The text excerpts begin with an article in the Manitoba Morning Free Press, September 3, 1906: “Water Commission Visits Shoal Lake. The members of the water commission visited Shoal Lake, near Kenora, on Saturday to ascertain its suitability as a viable source of supply for the city ... Soundings were made, the shores inspected, samples of water collected and an effort made to gain an idea of the country lying off towards Winnipeg ... This large body of water is practically the highest portion of the country ... There is practically no habitation with the exception of a few indians and an odd mining camp …”

(Again, the disregard for the presence of the Indigenous community is jarringly blatant here).

The Manitoba Free Press reports on April 30, 1919: “On the 5th of April, only a few weeks ago, the waters of Shoal Lake flowed into the mains of the City of Winnipeg. When the citizens and housewives turned on their kitchen taps it was pure, sweet, soft, and sparkling water that splashed into their sinks. For nearly four years, the construction and engineering went steadily and successfully forward ... An aqueduct of more than 96 miles long was constructed. Sums of money exceeding fourteen and a half millions of dollars were expended ... Tunnels were sunk and carried under the beds of rivers. Scores of miles of railway trackage was laid down to haul the material of construction. An army of men was employed ... [W]hen the water was finally delivered to the people of Winnipeg the supply from which they drew, the water district which had been created for them, was one of the largest and most notable on the whole American continent ... And the finished accomplishment, the Greater Winnipeg Water District, constituted one of the greatest pieces of constructive engineering in the history of Canada. Here is a water supply worthy indeed of a great western city …”

Professor of History at the University of Manitoba, Adele Perry explains in a Free Press article from December 13, 2016: “Shoal Lake 40 has been paying for our water for a century. In 1915, the federal government “transferred” more than 3,000 acres of Shoal Lake 40's reserve land to the Greater Winnipeg Water District for the sum of $1,500. The interests of the settler city were placed above those of indigenous people, even to lands supposedly reserved for them. For Shoal Lake 40, the consequences have been enormous ...”

Will Braun, Senior Writer for the Canadian Mennonite writes on November 19, 2014: “Winnipeg Mennonites follow their drinking water to its source. On Oct. 9, 2014, five carloads of concerned Winnipeg citizens – including two Mennonite Church Canada representatives – travelled 160 kilometres eastward to the other end of the aqueduct that has supplied Winnipeg's water since 1919. There, Chief Erwin Redsky and other community members shared their story ... Following the visit, Steve Heinrichs, director of indigenous relations for MC Canada, said, 'Winnipeggers need to know where their water comes from ...[and] make sure the situation is addressed.'”

Winnipeg Free Press Journalist Chinta Puxley writes on November 4, 2015: “Some Winnipeg councillors say the city has a moral responsibility to help build a road for a reserve that has been cut off from the mainland for the last century so the Manitoba capital can have clean water ... Coun. Jenny Gerbasi said the tour [of Shoal Lake 40] was powerful and suggested helping to build an all-weather road for the man-made island would be an important act of reconciliation ... After years of fighting for basic human rights, Chief Erwin Redsky said his people are finally feeling optimistic. 'There is a light at the end of the tunnel, and that light is getting brighter each day,' he said Tuesday. 'It's been 100 years and we're looking forward to a new beginning.'”

On December 18, 2015 Winnipeg Free Press Journalist Bartley Kives writes: “The sound of drumming reverberated around the legislature's grand staircase Thursday as all three levels of government agreed to end the century-long isolation of Shoal Lake 40 First Nation. The federal, provincial and civic governments formalized their commitment to build an all-weather road to the northwestern Ontario Anishinaabe community ... 'I never thought I'd live to see this' said lifelong Shoal Lake 40 resident Ann Redsky ... Redsky said she's been wary of making the crossing between her island and the mainland since she was thrown from a motorboat and nearly drowned in the late 1990s ... 'Everybody has a story. Every fall and spring is a dangerous time.' [C]hief [Erwin Redsky] praised activists for promoting the need to build an all weather road and thanked Winnipeggers for supporting it ...”

On June 4, 2019, Winnipeg Free Press, Journalist Kelly Geraldine Malone reports: “'This is Freedom Road.' Shoal Lake, Ont. - For the first time in his life, Chief Erwin Redsky won't have to fight for each small stone that lies along the 24-kilometre road that connects his First Nation to the outside world after more than a century of isolation. He looks down the long, wide, gravel land link and predicts it is his community's path to the future. 'This is Freedom Road.'”

For digital access to the book please click here.